- Home

- Simon Jimenez

The Vanished Birds Page 3

The Vanished Birds Read online

Page 3

He laughed.

“I do,” she said. “You’re attractive. More than those men, at least.” She nodded toward Sado’s table, the bachelor heads rotating slowly whenever a woman passed by. They both laughed, the laugh cut short when she put her hand on his. “And I like you.”

His breath hitched.

He hated that.

How one touch from her could undo him.

They didn’t walk through the celebration like last time. On Kaeda’s suggestion, they walked farther down the alley, away from any eyes, and went off the main road. They headed toward the millhouse. Inside, they walked past the rows of troughs where the seeds were mashed, up the steps to the loft, behind bound piles of purple stalk spines. It was different from last time, or the same, with Kaeda noticing new aspects of her; like how she refused to make eye contact when he was inside her, as though he was not there, or she was not there, she on some other planet, loving some other person. But despite her distance, still he gasped and bucked and held her like she was his own beating heart.

“Look,” she said when it was over, and they lay together, exhausted. She stretched his pubic hair between the comb of her fingers. He asked her what was wrong. “You have some gray,” she whispered.

She sounded almost sad.

In the morning, he offered to walk her back to the plains, but she touched his arm and told him she would prefer to go back alone. So he returned to the plaza, where he helped clean the trash from last night. He beat the cushions free of crumbs and fell in step with the others as they carted the bowls to the river to be washed. When overhead he heard the sky crack, heralding the departure of the ships, he did not look up. Wouldn’t. Not until the last of the green lines had faded away and it was safe to miss her again.

* * *

—

His mother passed away in her sleep at the end of the moisture season. It was her heart. A neighbor found her with one of his father’s old sandals gripped in her fist, which she had up until that night kept by the front door, as if at any moment the old man might return from the fields looking for them. Kaeda lit the pyre and tossed her ashes down into the moisture pits, and with those ashes his guts followed like lengths of rope, whipping into the dark below.

He slept that night with his head on Jhige’s lap. She stroked his hair as she hummed the old songs they used to sing as children. The songs children learn from their mothers, to help them make peace with the dark.

* * *

—

The dead were remembered, and the living went on. Soon their daughters were old enough to work. Elby, the stronger and more serious of the two, joined the hunters, and Yana, the talker, cracked her knuckles and set to work in the millhouse.

They were not the only ones with new assignments. After a back injury had rendered him useless in the fields—thrown out after he’d carried a heavy container of seed—Kaeda was assigned to the collections building, where he manned one of the seed scales, tallying the weights of the containers the farmers brought him. He worked around the growing paunch of his belly, distended from large plates of meats and pastry, his sweet tooth another new discovery with age. Yotto visited often, the violent past between them now settled. They were even able to joke about the time, years ago, when they fought in the dirt for Jhige’s love.

It was late into the moisture season when Yotto sat on Kaeda’s work table, fiddling with his hands, and asked him about their daughters. “Have they said anything to you? About…men?”

Kaeda shook his head, finding the man’s worry amusing. He told Yotto there was nothing to worry about, even though he knew Yana had her eye on one of the hunters; he saw no reason to trouble the man with things he could not change. “Best you keep your mind on other things,” he said.

Comforted, but not ready to leave, Yotto picked at the gray in his beard and asked how much longer Kaeda planned on working in collections. “You shouldn’t be here,” he said. “You were born for the fields. Everyone knows it.”

“Soon as my back is ready, I’ll be out there again,” Kaeda assured.

But when his back healed a month later, he remained with collections, having discovered that he liked being able to sit and rest. There he made the tallies while Jhige continued to squeeze the fields, her body a livewire network of muscle and tendon. When she lifted her containers up onto Kaeda’s scale, she would prop her elbow on his desk and brag about how long she had outlasted him on the field. “One year and five days,” she said, when he was forty-nine. “Two years and twenty,” she said, when he was fifty.

“Three and eighty,” he said, cutting her off with a smirk, when he was fifty-one.

She leaned across the desk and kissed him on the corner of his mouth. “I win,” she whispered, for even after all this time, their rivalry was still strong.

When he was fifty-two, at the end of the dry season, he sat on a bench in the plaza, alone, while the others attended Shipment Day in the fields. He wanted Jhige, Yotto, and their daughters to enjoy the event together without him, for once. In the plaza he watched the propping open of the long tables, and the building of the fire pit, and he wondered what Nia would think of him, now that his hair was a thick shock of white and his once work-hardened muscles were now hidden beneath a layer of sedentary fat.

Later that night, when the fire was at its peak, and they sat together at one of the long tables, still easing into conversation, he asked her this. She was younger than him by sixteen years now. Never had her youth been more apparent. Perhaps that was what she was thinking about as she studied him while rubbing her smooth cheek. “You look very distinguished,” she said.

“And you,” he said, “like yesterday.”

She smiled. “How long have you been waiting to use that line on me?”

“Five years,” he admitted.

They laughed, and after a toast, drank their bowls of spirits.

That was the last night they slept together. He had enough in him for one bout. As they lay in the chill night, clothed, he too cold to be naked, he wondered aloud how difficult it must be, to always be moving, always arriving at a place where your lovers were either old or dead. She told him it wasn’t difficult at all. And as her left hand formed and re-formed a fist, she said that the day she stopped moving would be the day that she died. She turned her head toward him, her brow knit, and asked him why he was laughing. He wiped his eyes and told her he didn’t know, though in truth he did, but didn’t wish to share the reason for fear of insulting her: that her words were absurdly dramatic. She was content to let the moment pass. Come the next morning, they parted without saying goodbye; both knew they would meet again soon.

When the governor passed away from a stroke the following dry season, it was time to hold the ruling elections. It surprised no one but Kaeda when he was elected. He had unwittingly begun his political ascent during his tenure in the collections building, where as he tallied the container weights the farmers learned his name, and spoke with him, and trusted him as one of their own, whose purple palms told the story of his field experience. He ran against the son of the deceased governor, an ineffectual man who ran solely out of the familial pressures of his aunts and uncles, who were hungry for a dynasty. It was clear from the outset which way the vote would swing; the governor’s son bowed out of the race before the final votes were even tallied, and spent the rest of the night in the bar claiming that the election was rigged from the start, buying drinks for anyone who would listen, though the few who entertained him were either not convinced or didn’t care. “My father was right in the end,” Kaeda said to Jhige the day they moved into the governor’s house on the top of the hill. “This place is mine.” He tossed the jar of finger bones into the moisture pits that afternoon, where it joined the rest of the dead, the prophecy fulfilled.

As governor, he made annual visits to the other villages to meet with the other leaders to discuss

trade agreements and field borders. Monthly coordination meetings with the appointed heads of the millhouse workers, the hunters, and the traders, paired with weekly one-on-one meetings to listen to gripes the heads had with one another and with him. And daily, at seemingly every hour, there was someone knocking on his door, a villager in need of mediation for whatever neighborly territorial dispute was waged that day, his house the new temple of grievances. All this he attended, including the walks through the fields, the first cutting of the hunted flank, the harvest speeches and benedictory words for all the newly born children. By day’s end he was drained, as was Jhige from her work in the fields, and when the sun was down and the air was cool, they would sit together on the porch and say nothing, staring blankly out at the village that was theirs, Jhige gazing at the sections of field still to be tended, while Kaeda’s gaze was lifted higher, at the field of stars, tired beyond measure, and wondering what could’ve been, had he been wiser in his youth—had he chosen his words with more care.

Months would pass without his noticing.

On Nia’s penultimate arrival, he gave his speech to the gathered crowd on the sacrifice the offworlders made, traversing time and space to spread their harvest. When the sky cracked and the green lines arrived and all the children whose names he didn’t know gazed up at the approach of ships with widened eyes, he was overcome not with nostalgia but an intense worry for these children, and the years of reckoning that lay before them. He wanted to warn these children that time was not their friend; that though today might seem special, there would be a tomorrow, and a day after that; that the best-case scenario of a well-spent life was the slow and steady unraveling of the heart’s knot. But he held his tongue. He let them enjoy the lights. “Let us welcome them with open arms,” he said.

Nia almost didn’t recognize him when she emerged from her ship, not until she was close enough to shake his sixty-seven-year-old hand. Her eyes widened, but only just, at the liver spots.

“It’s nice to see you,” she said.

They spoke by the fire like old friends. Commiserated about the difficulties of leadership. How draining it was to run a ship, a village. Took turns refilling each other’s bowls. They fell into an easy quiet, as they enjoyed the heat lick of the flame, and the bitter-strong taste of their drink, the anxiety Kaeda had felt earlier in the day settling down as he sat beside her and admired the dancers and the bonfire as it wavered through the hours. And when it was time, she gave him a brief hug before she returned to her ship, the warmth of it remaining even after she had left him.

He returned to Jhige at the long table, a little startled when, as she rubbed the lobe of her right ear between thumb and index finger, she observed that he and the offworlder seemed close. But she said this with no jealousy in her voice, the smile she wore one of amusement. A simple, matter-of-fact statement that cleaved him in two.

“No, not close,” he said, stealing a last glance at Nia as she walked away from the fire. “We’ve met only a few times.”

* * *

—

They would meet only once more, on his eighty-second year.

The year the sky broke, and the Fifth Village received an unexpected visitor.

It was the moisture season, and still many months to come before Shipment Day, and with it, Nia’s last cycle. The village was quiet but for the wing-rattle of night bugs and the distant howls from the forest. Kaeda was asleep in the governor’s house, his eyelids fluttering, dreaming of the day his father took him to see the ships, when he woke to a sonic boom that rattled the shutters. He sat up, dazed, unsure if he was still dreaming until Jhige’s trembling hand found his in the dark. He grabbed his cane by the bed. When they stepped out onto the porch, they saw it—a ball of fire peeling across the sky. The two of them watched with stolen breath as the ball arced downward and landed in the fields south of the village with an impact so great that it shook the earth.

A crowd had already formed in the plaza when they arrived. Amid the crying children and the parents who demanded answers Kaeda found Elby. He sent her and the other hunters to investigate the crash, the smoke of which he could see rising above the roofs in the dark distance. Elby sprinted off while he and Jhige went around to each family to calm them and assure them that they would be safe. The wait for news was endless. He sat on one of the benches, rubbing the ache from his knees, worried for his daughter, until she and her hunters returned through the village gates, carrying with them the body of a naked child.

It was a boy. His body was the only one they found at the site. All else was hot and black. “He was just there,” Elby said, “lying next to the rubble.”

Bruised and bleeding, but not broken, the boy was brought to the doctor’s house, where his glancing wounds were cleaned with wet cloth and wrapped in soft bandages.

He was a small, skinny thing—no older than twelve. Cheeks gaunt, his flesh so emaciated Kaeda winced, worried that if the boy tried to stand, his leg bones would snap in half. But there was no fear of him standing, for the boy was in a deep sleep, unstirred even by the loud and frantic conversation of everyone around him.

For three days the boy slept in the bed of the doctor’s hut while rumor spread through the village of his identity, be it demon, demigod, or harbinger of war; rumors born from nothing but fearful imagination, gaining weight and truth as they spread throughout the homes, from mouth to ear. Kaeda paid little mind to the rumors, and continued his visitations to the doctor’s hut despite the warnings of his advisers. “They once called me cursed,” he said to the sleeping child, holding up his scarred hand for proof. “Best not to listen to what they say. There’s no end to the stories that cowards tell.”

On the third day the boy woke from his long rest. Kaeda heard the toll of the doctor’s bell from across the village and shouldered his way into the hut, moving people aside with his cane, into the sickroom, where he found the child curled into himself at the foot of the bed, arms hugging his knees to his gaunt, brown chest, as the leader of the millhouse bombarded him with questions of where he was from and what he wanted. The boy was unresponsive. He sat with his back pressed against the board, peering at the strangers from above the ridge of his smooth forearms with eyes as wild as his knotted black hair. The millhouse leader’s voice rose with each question, red-throated, until Kaeda had had enough, and he ushered everyone outside, where he was swiftly surrounded.

Every villager was in attendance. All of them shouting variations on the same theme: that the boy was trouble and that he did not belong here. Shouting, until Kaeda raised his hand and silenced them. He looked out into the crowd. Of course they were frightened, he thought. This was their village’s first unexpected arrival since the time before Shipment Days. Even he did not know what to do. “I understand how you are all feeling right now. I feel the same way. I assure you that the child is only a temporary presence. Come Shipment Day we will hand him over to the offworlders. But until then we must remain calm, and remind ourselves that he is only a child.”

“Shipment Day is three months from now,” Goro, one of the fishers, said. “Who’ll keep him till then?”

The villagers exchanged glances while the dry grass skittered against the hot breeze.

“I will,” Kaeda said.

Jhige was less than thrilled when her husband returned to their home with the offworlder at his side. She gestured for the boy to wait in the living room and pulled Kaeda into their bedroom, where she let him know through whisper-shouts how furious she was that he had not consulted with her first. She listened to his apologies without expression; the explanation of his frustration with the others, and how they were so quick to judge the character of an unconscious child. And when he was done, she made a hard line with her mouth, and he worried that his words had made no impact, until she muttered, “Go see if he’s hungry.”

In truth he had always intended to be the one to take the boy in, ever sin

ce the night of his arrival, as he had a difficulty resisting anything that came from the sky.

Living with the boy was an adjustment for them both. He did not seem to understand their language, and never spoke in his own; a mute presence in their home, deaf to their attempts to help him. The first time he had to go to the bathroom, he relieved himself in his bed. Jhige washed the sheets while Kaeda showed him to the outdoor pots and pantomimed how to use them. He was unlike any child Kaeda had met. His movements were small and exact, his footfalls almost inaudible. It was easy to forget he was there at all, Kaeda remembering only when he would hear a small cough from the corner of the room and would see the boy covering his mouth with both hands, his shoulders trembling, as if expecting a beating.

They had fewer guests those days. Yana refused to pass the threshold of the house. Even Elby, fearless hunter that she was, made a point not to linger in the same room as the boy for too long. “The others are right,” she whispered, as she glanced into the living room, where the child stared out the window at the sky, as if he had never seen a sky before. As if it were impossible. “There’s something not right about him.”

“He’s a little odd,” Kaeda conceded. He rubbed the old scar on his hand. “But odd isn’t bad.”

The boy’s oddness was intriguing. Kaeda took the child with him on his long, rambling walks beyond the village, both to give Jhige some air, and to scratch at the mystery of him, and see if he could not make some connection. It was a game of sorts. The boy followed him without resistance, almost unconsciously, snapping from his trance only when Kaeda would reach into his satchel and hand him a sweetcake.

During those walks, Kaeda spoke enough for the both of them. First there were the gentle, probing questions. Questions of where the boy was from, if he had family. And then, when it was clear that the boy would offer no answers, Kaeda spoke about himself. He started with the simple facts. As they climbed the foothills with his cane and the quiet boy’s careful footstep, he shared the names of his parents, and how he had known Jhige since he was a child. How he was governor, and that it was his job to keep everyone safe. Over the days, and weeks, the longer they walked, the more he shared, as if the boy were an empty bowl that he was pouring his memories and thoughts into, all with the knowledge that the bowl did not understand, or nod, or question. In the twilight hours above the fields he indulged in sentimental thoughts; thoughts Jhige often teased him for, but that the boy took in as he did the breeze and the light. Childhood adventures in the yellow fields. The difficult harvests. And quietly, at dusk, in a murmur, the fears he’d carried with him over the years.

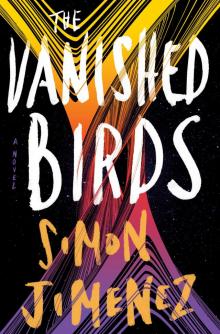

The Vanished Birds

The Vanished Birds